Didja read this letter in Harper’s? Wanna talk about it?

Read it first.

Seriously, please read it.

Then we’ll have a dialog.

I want to make a dialog. How? I’ll pull some tweets and respond. That’s a dialog of sorts. It’s as close as I’m getting, anyway.

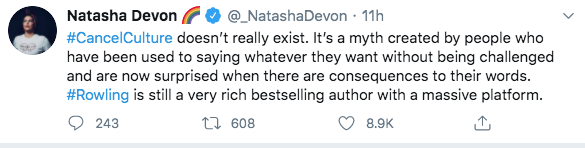

I tried to pull tweets that represented the bad arguments made about the letter. Please know that I’m not attacking these individuals, I’m disagreeing with their ideas. Please also know that the snipped tweeters in here are not the only ones making their arguments, and they are not to blame for the creation or propagation of these ideas. LOTS of people are expressing the same thing, and I’m not looking to pin the ideas to individuals here.

A notable omission from this discussion is ANYTHING referencing Nazis. Both sides jump to comparing both sides to Nazis, either directly or indirectly, and I’m just not having that today. If there’s one agreement I’d like to see, it’s both sides agreeing that calling the other “Nazis” is taking things…not too far in a moral way, too far in a “c’mon, guys” kind of way. Lining people up and shooting them into a burning ditch is a far cry both from cancel culture and from people saying things that are received as anti-X or X-phobic. I think we can hash this one out without busting the Nazi card. Let’s save that for something else.

Let’s look at what’s meant by “challenged” here.

Challenging what you say, in these terms, is telling on you to your boss, even if your actions were legal and had nothing to do with your employment. It’s asking/demanding that you be fired for your expression.

Is that challenging what someone says or their beliefs?

Let’s say we were debating, I don’t know, veganism. And you made some good points about the benefits of a vegan lifestyle. In response, I blew up your car. That’s not really challenging what you’re saying, it’s punishing and threatening you. And what’s sneaky about this type of threat is that it’s not a threat that prevented you from saying something, so people walk around like it’s not a problem. You still got to say you’re piece, therefore there’s no problem.

The threat is the problem. The threat applies to you in the future, so every time you go to talk about vegan recipes, you stop. And maybe you keep your mouth shut because although I might love to hear about your protein-packed hummus, is it worth the risk? The threat also applies to other people who have not yet spoken their minds, and now perhaps won’t because being an outspoken vegan can result in having your car blown up.

When I moved the debate out of the realm of ideas and into a decision to punish you for your ideas, I didn’t really engage with your ideas or challenge them. I punished you for your expression.

The issue with this statement is built into the letter. Cancel Culture means different things to different people. I agree, it’s fine to dislike someone’s book and to express that. It’s fine to challenge someone’s ideas. But I think there’s a line between disliking someone’s novel and emailing their boss to try and get them fired. I think this latter version is where the letter was going, but I don’t know that it was made as clear as it could’ve been. I think there’s a big difference between outrage and attempts to get someone fired, but I don’t think the letter did a great job making that difference clear.

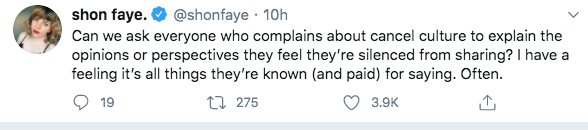

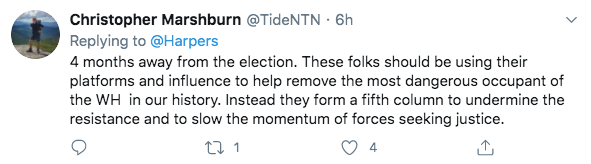

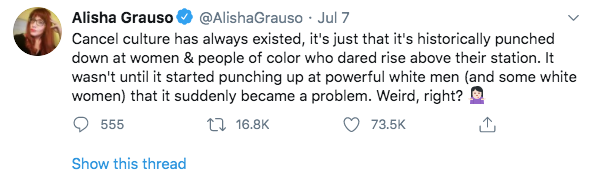

This is a common argument I’ve seen go both ways. On one hand, if you’re a powerful person and you say something bad, you’re an enemy because you are not using your platform to change the world for the better. This also applies in some cases if you have a platform and choose not to use it. The concept behind the saying “You can’t just not be racist, you must be anti-racist.”

On the other hand, if you speak out about something that will not harm you personally, then you’re complaining about nothing? That seems to be the assertion here.

Colin Kaepernick’s gestures and statements, I would argue, were designed to help others who didn’t have a platform more than they were designed for personal gain. I think many applaud or ask other celebrities and wealthy people to do the same.

Before you get all keyboard-y, I recognize that what’s happening here is not the same as what Colin Kaepernick did. It’s not moving the same direction, nor is it the level of individual risk. The principle is the same, the idea that those who have the ability to speak up should do so.

I see this letter as people in positions of power doing what we often ask of people in power: Using the platform to say something.

So, which one is it? Do we want people with big platforms to help those who don’t, or do we want people to only speak about those things that affect them on a personal level? Is it good for Metallica to speak out against piracy, or is it bad because they’re already rich?

We pretend it’s about how people use their platforms, but it’s not. It’s about the message. If someone fails to deliver the message we want, we can’t attack them for not using their platform, so we attack them for sticking their nose where it doesn’t belong.

Recognizing that you don’t like the message is fine! But let’s talk about the message then, refute that, rather than dancing around the concepts of who is empowered to talk about what and who has the authority to speak on the issue. By the way, the list of signers definitely have the authority to speak on this issue (more on this later).

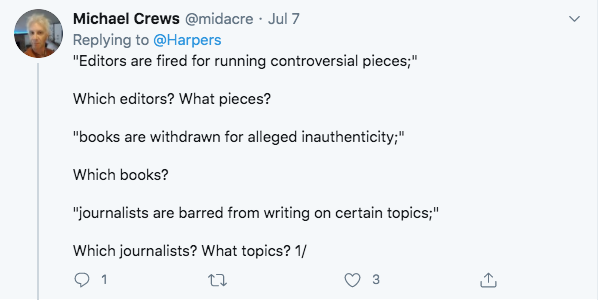

I almost fell into the trap of actually answering these questions!

I’ve seen a lot of responses like this. These are dumb. Because if you actually want to know, you can find them very easily. Don’t ask a question just because you want to waste someone’s time. This is a roadblocking technique. “Prove to me, someone who is obviously not interested or invested, that this is a thing.”

More to the point, this is a group of creatives from lots of different perspectives telling the world what’s happening behind closed doors in their industry. If this small sample size of a large industry all agree that they’ve seen or experienced this, it’s reasonable to assume this is happening. If others in the industry want to refute that this is happening, that’s fine.

What this does is attempt to force a discussion of the data as opposed to the idea. But this is not complicated scientific data that requires peer review, and it’s not data that seems manipulated here. It’s not even data, it’s qualitative narrative. Just google that shit, find out that it’s happened.

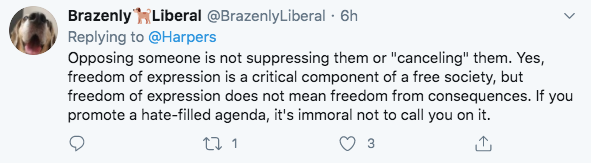

A sure sign that someone’s part of the mob is their advocating for mob justice.

This is one of my least favorite truisms circulating right now: Freedom of expression does not mean freedom from consequences.

It always reminds me of going to KISS mini golf in Vegas. The surly teenager behind the desk, who had the ultimate job for a surly teenager, said, “You can pick any songs you want, and we’ll play them. As long as they’re KISS.” She also advised us NOT to get the pizza. We did not, and I think that was some of the best advice I’ve ever received.

Freedom of speech doesn’t mean freedom from consequence? Let’s put this another way: Freedom of religion is not freedom from consequence. So, nobody’s stopping you from being, say, Pentecostal, but you should just know that being Pentecostal comes with consequence.

Is that really freedom of religion?

Your car can probably go over 120 MPH. But doing so comes with consequences. Does that mean you’re free to drive as fast as you want?

A woman has the right to choose. But if your community finds out you had an abortion, they may pressure your boss into firing you or create a work environment so hostile that you have no choice but leave.

Is that really the right to choose?

Having the physical ability to do something is different from having the freedom to do so. And consequences absolutely negate freedom. Just because consequences come AFTER the action does not mean they’re non-restricting.

The problem also goes deeper because “consequences” is vague. And vague consequences mean that people can’t make informed decisions. I know what is likely to happen if I no-call, no-show at work. I know what the likely consequences are, and the ceiling for those consequences, if I were to use a piece of unlicensed music in a commercial for one of my books.

Vague consequences and rules for when they’re applied means I may suffer consequences that I would have avoided if I’d known they were coming. Or, I may have made a different risk/reward decision if I knew the level of consequence.

That’s the thing about these consequences: They aren’t known on the creative side, and they’re not predictable by the audience side.

This means that consequences are unpredictable, and therefore many will make the choice to not roll the dice at all. And that is suppression of speech. Consequences are suppression. It’s like the kid argument, “I’m not going to punch my brother, but I am going to make a punching motion and walk in his direction.” You’ve semantically cheated the mechanism, but your brother still got punched. Suppression is the impact, even if that wasn’t the intention of “consequences.”

Your reaction to that may be “good.” And that’s fine. But recognize that you’re having a positive reaction to suppressed expression.

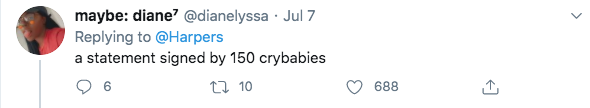

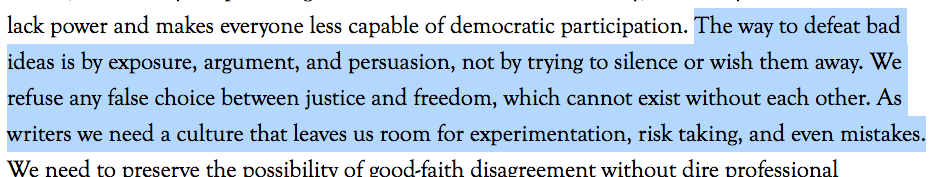

A classic tactic to avoid discussing an idea is to trivialize it. “This is beneath notice, so it’s not worth discussing.”

If you think this is a list of 150 crybabies, I have to ask whether you know who Salman Rushdie is. Because he signed this shit, and he knows a thing or two about expression-based oppression.

If you don’t see this as directly related to politics and upcoming elections, I’d refer you to the 2016 election and the issues Nate Silver had after he predicted (correctly) a higher likelihood that Trump would win than most every other outlet. He was lambasted, and he was even accused of causing the election to go wrong. Which is ridiculous, and the reality is that he told a truth people didn’t want to hear.

The ability to look at hard truths and say hard things is tied directly to politics.

Another tactic to stop a debate is asserting that the topic is not THE MOST IMPORTANT issue at the moment, therefore it should be off the docket.

Let’s be serious, there’s a crisis in policing in this country. Also, my garbage stinks and needs to be taken out. I can’t get away with telling my girlfriend that I won’t take out that garbage until there’s justice for Breonna Taylor. That’s not gonna fly, and it exposes the untruth here, that there can only be one thing to care about, or that it’s even possible or desirable to care about only one thing. And just because these creatives signed this letter does not mean it’s been the primary use of their energy for any significant period of time.

It’s also a mistake to think that free expression and criticizing government, whether that be in prose, protest, or what have you, are not tied together.

Harpers, a magazine barely anyone reads, should DEFINITELY fill their pages with unknowns expressing their opinions. Also, Nike should discontinue Jordans and make shoes based on my neighbor.

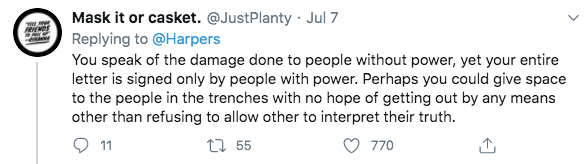

It’s precisely because they are powerful that this statement needs to come from them. The powerful speaking out about something they’re above helps others. Those who aren’t incentivized to see something change, because the current system is fine for them, their speaking out highlights that there’s a problem serious enough that it’s not about their individual income.

I think we also need to recognize that it’s not always a power dynamic, and not every instance is about amplifying a small voice. Sometimes it’s good to hear what thought leaders are thinking about in their specific area of study. I don’t really give a fuck what Rando X has to say about writing horror novels. I DO care what Stephen King has to say about it. Because he’s done it, he’s proven he can do it, and there are good reasons to listen.

It’s the reason everyone flipped out when they asked Martin Scorsese what he thinks of Marvel movies. We know the guy knows a thing or two about making movies, so his opinion on movies is relevant. And we can’t take his unpopular opinion and say, “Well, he doesn’t know anything about this.” He absolutely does. And the signers of this letter absolutely know something about free expression.

I also think that calling the 150 signers “people with power” is a pretty ballsy claim.

First things first: Ignore the JK Rowling! That’s to stir up controversy, that’s why her name is in the headline. Instead, notice Salman Rushdie, who knows being an oppressed writer better than most. Dr. Atul Gawande, an amazing thinker, writer, and innovator in medicine.

Notice Margaret Atwood, who up to today, has had the label “prescient” applied more than most and has done a good job living up to it. If I told you yesterday that Margaret Atwood was going to say something about freedom or liberty tomorrow, would you feel like this was something worth noting?

Notice Garry Kasparov, who lived under a very oppressive regime and should not be ignored on the topic of speech.

Notice Malcolm Gladwell, and do more than notice, consider how what he does necessitates some level of freedom.

Notice that all of these people are agreeing with David Brooks on this one.

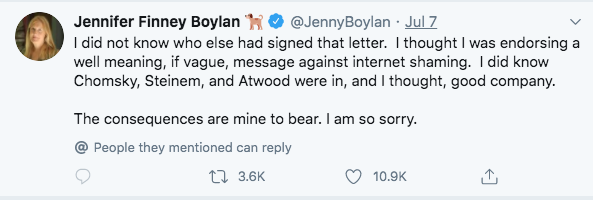

JK Rowling is the big problem here because this is now being read with an anti-trans lens. Without wading into Rowling, I think it should be known that (according to this signer) the signers of this letter did not know who all the other signers would be. I tend to believe that the signers probably didn’t know all of the other 149 signers. That seems very likely.

This is important because A) This is not individuals throwing in with each other and their histories, it’s individuals throwing in with an idea, and B) It’s proof that agreeing with a bad person on a single issue does not make you a bad person.

Unfortunately, JK Rowling’s signature probably weakens the statement a bit. Not because of her views, but because the story becomes about her. Now we have to talk about whether this is all an anti-trans letter in disguise. Whether there are “dog whistles” here and that what’s behind the curtain is, essentially, a bunch of people who want to use free expression to trash trans rights.

My hot take: Dog whistles are the backwards masking of 2020. “You can’t hear it, but it’s there, and it affects how you feel about something.” Or they’re meant to rally a community which, far as I can tell, has already rallied to the extent they’re going to rally. Why does JK Rowling need to use a dog whistle when she’s straight up screaming the dog’s name on Twitter every couple days?

I think this letter could be interpreted a lot of ways, if you choose to interpret it. But I think that’s overinterpretation. Overinterpretation is what that one college English professor always did, where everything you read was a penis. Frankenstein is a penis metaphor. Don Quixote’s windmills are penises. Shakespeare’s collected works are one big penis description! When you overinterpret, you see penises in things like skyscapers. Which is silly. I don’t know what all penises look like, but mine is not a giant, glossy vertical shaft with many right angles. Buildings being “phallic” is so dumb. Okay, go ahead and make sturdy, efficient buildings of another shape. I’ll wait.

If you see an anti-trans (or anti-any-demographic) message here, that’s your opinion, and I don’t agree. I think the letter is very concise and clear, and I think any investigation into what it “really” means is more revelatory about the investigator than it is about the text.

To put a finer point on it, I started this letter having the opinion that trans rights should be a thing, and trans people should be treated like people. I don’t see how that’s complicated, and I don’t fully understand why it’s controversial and have a hard time arguing in favor because I don’t even really get the arguments against. When I finished the letter, I felt the exact same way. I don’t think this letter is a brick in the wall blocking trans people from their rights, either in intent or impact.

Again, lots of these where it becomes a racial or other demographic issue. I looked through the signers, and they’re a large mix of nationalities, genders, and races. So to suggest that this is a “white people problem” is incorrect based on the fact of the signers and their identities.

A popular mode of critique of ideas is to tally up the authors, check for character flaws, check the demographics, and then, if there’s time, read the contents. This is exactly the sort of thing this letter is speaking out against. Fortunately, this tactic doesn’t work well on this letter, from a demographic standpoint.

But let’s say this was true. What then?

Something that’s important to recognize here is that any regulation, wielded badly, will affect protected classes in more devastating ways than it will affect powerful white men.

As an example, a hotly-debated topic in the world of libraries is whether or not a library would let a white power group use their public meeting room. Without getting too far into the politics of libraries and communities, just know that this has already gone to court more than once, and courts have always ruled that yes, white power groups must be allowed to use meeting rooms. Libraries are government funded, so there are different rules.

However, it’s still debated in library circles, and one argument I make in favor of hate groups using the meeting rooms is that I’ve yet to see an effective policy that would eliminate hate groups but could not then be turned against other groups who are in more desperate need of free meeting spaces.

When designing policy, it’s always important to ask a couple questions. One, will this hurt the people it’s designed to protect? And two, what happens when this policy is in the hands of a very different staff who feel very differently?

So, if we build the power of cancel culture, what happens when cancel culture is dominated by people we disagree with? When a conservative groups figures out how to wield it more effectively, how are we going to deal with that?

And, does it hurt people it’s designed to protect? What about Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s place in the world of words and ideas? Dave Chapelle oscillates between cancellation and hero status every few months.

Part of the theory of privilege has to do with the ability of the privileged to skate by when they commit violations, and they have an increased safety net that allows them to bounce back. Perhaps your average white, male editor has a big network of people and can land another job pretty easily. Perhaps he’s part of a “good ol’ boy network” that finds him another cushy gig in no time. Most proponents of the ideas of privilege would probably agree with those likelihoods.

And if we buy into that theory, then the young woman of color who writes a novel that is pulled from publication doesn’t have the same privilege, and she’s not able to bounce back as easily. Or maybe at all. Meaning that the way we’re regulating speech does more harm to the underprivileged than the privileged, which makes it an unjust method.

This is not me equating causes or saying that denying the humanity of trans people is right. This is me saying that at the moment, progressive ideas have the momentum to get people wearing Black Lives Matter clothes at work and to get people fired for conservative views. This is a historical moment, and it’s still only a moment.

What happens in 5 years? What happens when a cause you believe in is punished? Are you confident that the progressive movement of speech goes one way, that it’s not a pendulum that will swing back or a gizmo that moves in far more than two directions? Are you confident that inequality will be eliminated before the pendulum swings back, and therefore the effects won’t be disproportionate?

This one’s popping up a lot, too.

I’m very exhausted by the amount of arguing against free speech that is based on the idea that only racists and bigots use the right to free expression. This is not only shortsighted, it’s factually incorrect.

Let’s look at some positive examples:

Island Trees School District v. Pico (1982)

The Supreme Court ruled that officials could not remove books from school libraries because they disagreed with the content of the books’ messages.

Texas v. Johnson (1989)

Flag burning as political protest is a form of symbolic speech protected by the First Amendment.

Watchtower Bible and Tract Society v. Stratton (2002)

City laws requiring permits for political advocates going door to door were unconstitutional because such a mandate would have a “chilling effect” on political communication.

But more than court cases, I think we often miss the everyday instances in which speech is used.

I encourage you to think of your favorite album. Do the lyrics talk about drugs, sex, violence, and/or any illegal acts? Has your favorite artist ever been convicted of a crime? If so, your favorite album probably would not exist without freedom of expression.

Does your favorite book contain crime? Immoral or illegal acts?

Do you express yourself through a bumper sticker?

Do you ever wear t-shirts that express something?

Another example I often gave in the Intellectual Freedom class I used to teach, the ability of people to question government, law, policy, and each other is rooted in free expression. Marijuana use and the sale of marijuana was illegal for a long time. However, the library and bookstores could still stock materials about the cultivation of marijuana plants. They could still get High Times. I’m of the opinion that information about things like marijuana is critical to getting the rules changed. For Colorado, it’s important to know what the real effects of marijuana might be on the human body, and in order to find out, people need access to information. It’s important to know what growing and cultivating marijuana would entail. It’s important to know what the economic effects might be. Without access to information and opinions that speculated and provided background on places where the law and morality might be wrong, I think changing an unnecessarily-restrictive law would have been far more difficult if not impossible.

By the way, I always used the marijuana example instead of Civil Rights. But apply the same logic: your ability to question things that are wrong is tied to your intellectual freedom.

The law isn’t always right. The majority isn’t always right. And access to opinions, ideas, and facts that go against the grain are needed.

It’s not always about the rights of the speaker, either. Free expression and intellectual freedom are tied. When someone’s book is not published, it not only restricts the rights of that person to express, it restricts the rights of an audience to experience that book, absorb its messages and information, and make decisions for themselves.

Jordan Peterson’s book is a good example of this. I heard a lot about this fella, read some of his book, and formed my own opinion. Which is that most of what he says is innocuous pop psychology, and there’s nothing of a depth that I felt any need to read or explore further. I don’t think he’s the antichrist, and I don’t think he’s our savior, either. He’s an Oprah for young frat boys, and maybe I don’t need his message, but maybe young frat boys do need to be told to make their beds. If I’d read articles on one side, I would have come away thinking he was an awful man who was driving marginalized people into the ground. If I’d read articles from the other side, he’d be a martyr for the cause of…well, I’m not sure, but something. After looking for myself, I found what I usually find: the person is neither as good or as bad as they’re made out to be, and they are more moderate than I was led to believe by people paid to write articles about something.

Suppressing direct speech isn’t just about suppressing the speaker. I’m not concerned about Jordan Peterson. I’m concerned about what seems to be a desire to turn over our intellectual curiosity to Slate, Daily Beast, and Buzzfeed. Let them do the legwork and let us know how to feel about it.

I do not want to decide how good or bad something is based on what Slate tells me. I want to see for myself. I definitely don’t want to be unable to access something because Random House is scared of what Slate’s opinion will be.

Yes, heinous ideas and expressions are protected. I don’t really want to get too deep into it here, I just want to say that I am of the opinion that our government and culture are not sophisticated enough to make a lasting, permanent distinction between “good” and “bad” expression, and that’s why the default position on expression needs to be allowing. To put this in a more typical way, if speech is going to be limited, who will make the distinction, and do you trust them to make the right choice? Second, who will make the choices 25 years from now, and are they the right person?

When it comes to making choices for me, I’m the right person. And this should apply to everyone. You are the right person to make choices for you, nobody else.

The Biggest Mistake

It’s generally a mistake to say something genuine and direct on the internet, to “the internet.” A dunk is more important than a truth, especially an emotional truth. Many, many responses were things like eyeroll gifs and generally weird bullshit.

There’s no snark or takedown embedded here. It’s just a statement of feeling. And that’s where it fails.

The biggest mistake you can make on the internet is to fail to be entertaining. This letter is not entertaining.

What Are Some Other Options?

Whether or not you believe in cancel culture or the ideas in the letter, I would like to suggest some options outside of calling someone’s boss. Because I think there are positive options that accomplish the same goals of decreasing the power level of someone you don’t care for while also increasing the power level of someone who says things you like or think are important.

You and I can’t end or continue cancel culture. Cancel culture is an idea, not a person. What you can I can do is decide how we interact with expression we dislike.

- Good Consequences. Rather than creating consequences for “bad” expression, consider methods of incentivizing “good” expression. Don’t like what David Brooks says? You don’t have to try and get him fired. You buy someone else’s books instead. Someone who holds opposing views. That’s another way to use the free market. Talk to experts on behavior, they will tell you that incentivizing “good” behavior works a lot better than punishing “bad” behavior. Buy someone else’s stuff. Ignore his columns. Ignore columns ABOUT his columns and retweet something excellent instead. Remember how grade school bullies have to learn that pumping yourself up is accomplishable without shoving someone else down and standing on them? The same idea applies. Pumping someone up and taking someone down are mutually exclusive activities. Free market is not you emailing someone’s boss. The free market is about you buying someone else’s work.

- Read More, Read Longer. Read the source material. Read it BEFORE you read someone’s take on it. Books > articles > tweets.

- Stop Worrying About Morons. Oftentimes I see handwringing along the lines of “I understand why this is bad, but what about some other person I’m going to invent right now who’s not as smart as me?” First of all, don’t invent hypothetical morons. Real morons are all over. No need to create more. Second, this is the new “Won’t somebody think of the children?” We can’t childproof the world, and we can’t moronproof intellectual discussion. Plus, I think “moronproofing” is really an excuse for someone to put their interpretation out there and spin it as altruistic. “I’m helping by limiting expression because not everyone will understand what’s being expressed.” You’re not so smart that we need you to rescue us.

- Non-Corporate Healthcare. Seems tangential, right? But if your basics of living, like healthcare, are not tied to your job, then I think the “consequences” created, even in the extreme case of losing a job, are different. The way things work currently, losing one’s job isn’t just about prestige, it’s about access to healthcare. I don’t think most of us would advocate for cutting someone off from healthcare based on their opinions, but that’s a side effect of what happens when we look to affect someone’s employment. If we have healthcare and a better welfare system in general, employment is not directly tied to someone’s physical survival, and perhaps it means something different to go after people’s jobs. Perhaps this becomes a more appropriate measure. If your job holds the healthcare strings, and if they can fire you based on morality, then it’s fair to say your job can enforce your morality. That seems wrong to me.

- Think About Publishers. If you dislike an author’s personal views, maybe you need to stop buying things from their publisher. Ouch, right? That one’s going to sting. But moving away from an author while still buying and reading from a publisher is like crowing about moving away from Facebook while still being a hardcore Instagrammer. You’re still supporting the overall company. But more than moving away from publishers, I would encourage you, if you’re in this camp, to move TOWARDS publishers with missions you can respect. Be active, be intentional. If the morality of the publisher is important to you, start there.

- Question Your Own Morality. You don’t have to change your morality, just recognize that questioning your morality is okay, even beneficial. Challenge yourself. When someone says, “Cancel Culture is X” ask yourself whether you agree, and then ask yourself why. Pretend like you’re discussing it with someone who has heard the typical arguments. Try and come up with your own reasons, your own wording, instead of using tired cliches. Cliches exist for a reason, but coming up with your own logic and looking deeper into an issue will help you gain a deeper understanding and better prepare you to make the case.

- Allow That People Can Be Right About Some Things and Wrong About Others. One of the problems with the current method of evaluating expression, checking out the person’s “controversy” sections on Wikipedia before thinking about what they have to say, is that you might miss out on something important, a new way of thinking, that’s in no way harmful. In the above case, because someone is wrong about trans rights doesn’t mean that they (and 149 others) are wrong about free expression. Challenge yourself to look at things from an ideas-first perspective. Think about the ideas before you dive in and find out the nasty stuff about the individual.

- Marie Kondo That Shit. You know how Marie Kondo tells you to thank your shoes for doing a good job today? Okay, it’s a little weird, but it has a good effect. Thanking my car for getting me to work every day has changed how I feel about my car when it breaks down. When your car breaks down, it’s like it’s always breaking down. But if you get used to acknowledging that your car works almost all the time, you can allow that it’s not going to work every single day forever and ever. Get used to looking for positive examples of free expression in your life. Get used to being thankful for times when free expression was a positive thing. When you put on your Love Trumps Hate shirt, think about how you’re glad that this is possible. When you play a game where you blow someone’s head off, think about how it’s good that people recognize the difference between this expression and wielding a gun in real life. See if recognizing the usually-unremarkable instances of free expression changes how you feel about free expression.

- Find Something Out For Yourself. Who is someone you’re afraid to read? What is an idea you’re afraid of? What’s a movie you were scared off of? Find out for yourself. Have an experience where you were told something, and you say, “Let’s see.” Almost every time, you’ll find that the experience was neither incredible or abysmal. It’s usually middle-of-the-road. Having this ho-hum experience is extremely valuable.

- Interpret More Than Once. Most readings of things online are assuming worst intent. I know, everyone is exhausted and “benefit of the doubt” has become something terrible, somehow. So I don’t ask that you give something benefit of the doubt. I ask that you read with two lenses. Go ahead and read with your current, worst case lenses. Then, read again, and just ponder “What would be the best possible intent here, if I had to make that argument in a debate class or some shit?” I’m not asking anyone to land one way or the other. Just be open to the intellectual exercise and see how it feels. Try and figure out just how pessimistic your normal lenses are.

- Actual Homework: Do me a favor, look up the novelist who had the biggest negative effect on the world. No cheating, no picking a dictator who also wrote a novel, a political pundit who also wrote a novel. No fair picking “the guy who wrote the Bible” (that’s more like an instruction booklet than a novel). Pick a novelist, explain their effect, and demonstrate how things would have been better had this person NOT written a novel. Just as a caveat, I often hear about the idea of normalizing, but I’m not totally convinced. I think most artists write about things that are already normalized. Perhaps fight clubs would not have been as widespread as they were without Fight Club, but I think the ideas of male violence and men being unable to express tenderness with each other were not created by Chuck Palahniuk. They were reflected. Maybe these issues were provided a different form, but criticizing the form is killing the messenger. So let’s hear it. Worst novelist?

- Make Something. Write a book. Draw a picture. Design a board game. Make something. Exercise your artistic expression. Many, many people don’t really make much, and then they have strong opinions on how other people should do it and how they should feel about it. You have every right to critique the opinion of an author, but that critique means a lot more to me if you’re also an author. Plus, you’ll just be happier. You really will. Making and critiquing are not mutually exclusive, you can do both. I just suggest that making more stuff and critiquing less is better. Adjust your ratio. And make things that make use of your freedom of expression. Dangerous things. Try using your freedom of expression before you decide its value.

The Personal Section

I’m saving this section for last because it’s the least important.

Why do I care about this stuff?

I worked in public service for over a decade, and whenever I worked with the public, I avoided debating anyone who asked for help.

One reason, my job was as a public servant, and I took that seriously. Meaning: if someone felt I was judging them or their ideas, maybe next time they don’t ask for the help they need.

And it may not be THAT person I affect. Perhaps another member of the public nearby hears us talking, and maybe we are in agreement, but this third party takes in what’s being said and doesn’t feel like the library is as home-y as they thought.

The other reason for avoiding discussion was more self-centered: debate when you’re wearing a nametag is never even. Because, let’s say we got into something, the person on the other side of that desk always has the option to talk to my boss and create consequences for me, and I don’t have that option. I might not get fired, but maybe I get a poor performance evaluation, which affected the small raises I got each year. Maybe I don’t make my way onto a committee that I really should be on because I’m earning a reputation for being difficult to work with.

Before we get too far, let me just say I was not typically presented with fantasy topics. By this I mean people did not come up and say things like “Can you believe they’re letting trans people into the military now?” Or “Can you believe they let Mexicans use the library here?” Lest you think I stood by while racial slurs flew out of someone’s mouth, that just didn’t happen. Sorry, I can’t tell you a story of heroism, of throwing myself at the defense of someone else. It wasn’t that way In 15 years, I never had to throw myself between an ICE agent and a library user, nor did I have to fly in and protect a gay student from his peers. These things never happened. I was not presented with these choices.

I made my way into libraries by chance, and I went further in the field because I felt that libraries were very interested in intellectual freedom, a topic I was also passionate about. I’ve always been of the opinion that more speech is better speech, and what people need is not regulation, they need access to the materials that allow them to make their own decisions. They need enough exposure to information to build their own bullshit detector.

More recently, I’ve felt that the library and I are disagreeing on the issue of intellectual freedom. In online discussion, I’ve seen things I would not have expected previously, and I’ve seen them happening in more 50/50 ways. For example, should libraries get rid of JK Rowling books because she’s seen as transphobic? Many, many librarians, to their credit, disagree with this action even if they agree with the politics behind the idea. But there is an increase in the number of people who feel that an action like this, removing Harry Potter from a library, is justified and just.

I’ve seen similar debates about Donald Trump’s books. I’ve seen tougher debates on books promoting conversion therapy. We had one in our collection, and I had a good discussion about it with a few coworkers. We did get rid of it, but we got rid of it because it was in disuse, not because of the ideas it presented. We discussed whether we would keep it if it were popular. I felt that while conversion therapy is a bad idea and illegal in some places, library users have the right to look at information and make their own decisions about something. If laws are to be made about conversion therapy, people should have the right to know what’s being discussed and ruled out.

Also, as a specific note, our book was an account by a man who said it “worked” for him, and it was promoting the idea to other adults, not to children. I think this is really different. An adult has agency to decide which path they take.

This is such a tough thing, and it requires a level of empathy that’s hard to find. Because it’s not total empathy. It’s enough empathy to understand someone’s struggle, but not so much empathy that you get personally involved.

But imagine. An adult, gay man who is also deeply religious. This man feels that his religion and his sexuality cannot coexist. He wants to explore what other people in his shoes have done.

Let’s expand that scenario. An adult, gay man who is also deeply religious. I don’t think sexuality is a choice, but I do think religion is a choice, and it’s this man’s choice to make, not mine. I would like to provide him materials about different religions and non-religious paths, but it’s his choice which materials he’ll view, and it’s his choice which path he’ll take. This man feels his religion and sexuality cannot coexist. Again, this is his choice, not mine. I would like to provide him resources that give him alternatives, but the choice, as always, is his. He wants to explore what other people have done. I think it’s to his benefit to have the option, should he choose, to explore what someone else in his situation has done. I can’t pretend I know what it’s like to be gay OR deeply religious, and I am not the right person to make the decision for him. I am not a religious scholar or figure. I am not an expert in human sexuality or any kind of sociology or psychology. I am an expert in intellectual freedom, and I am the right person to provide a range of option and opinions and to let him make his own choice.

I think a lot of people, instinctually, will say, “I would just tell this guy fuck his religion and be you!” There’s a need for that kind of person and idea in society. And there’s a need for me, the person who says, “Here is a lot of information and opinion. I am not judging you or pointing you in a direction. I’m giving you the support to make a decision of your own.”

In fact, I think this person is very much in need. I think one path to a better life is for people like this hypothetical man to not only make this HUGE decision, but to learn decision-making techniques that allow him to have confidence in his choices. If I make a decision for him, he’s robbed of that confidence, and he’s robbed of the tools to make future decisions.

This neutrality is in question often in libraries. That’s a topic for another time. But what I want to say about it is that if we decide to trash the intellectual freedom in the interest of doing what’s right, we have to ask whether that does more harm than good. It’s usually not as easy as removing a book called “White Power for Dummies.”

Does it help or hurt our community if we refuse to carry Donald Trump’s books? Does it help or hurt our community if we refuse to carry any Weinstein-produced films? Does it help or hurt our community to take Junot Diaz and Sherman Alexie off the shelves? Does it help or hurt our community and early literacy if we remove Harry Potter?

There is no answer. Because for some, it helps. And for some, it hurts.

And my take is that intellectual curiosity is the only way people can make good decisions. Just about every exercise/training book has some good stuff in it and some bullshit. The way you start to figure out what’s right is you read dozens of them, see the commonalities, and start with those. When you read a dozen books and all agree that squats are a critical part of fitness, you can feel pretty good drawing the conclusion that, to the best of everyone’s knowledge, squats are a good idea. When you read one book, one way, and get dogmatic about it, that’s when you’re in trouble.

I’ve been proud to provide the community a chance to explore. I think the library is one of the few institutions where this is possible. I challenge anyone to name an institution or outlet that’s gotten intellectual freedom more right.

So it bothers me to see a move towards something that does not resemble intellectual freedom. Others have moved away from it, but I do not think we should follow. As poles stretch in opposite directions, our job is tougher. Providing information and ideas from both poles and every spot in between is harder. But that’s no excuse to abandon the pursuit.

Intellectual freedom and freedom of expression also mean something to me personally. I often exercise my freedom of expression and intellectual freedom. I like to read things that I disagree with and do so often. I like to read works by and about bad people. I think it’s important that I be able to access information and opinions on current topics and esoteric, weird shit.

And I’m not old, but old enough. I think I’ve seen the cycle here. When I was young, conservatives were limiting speech on a moral basis. Music was a primary concern, violent video games, Marilyn Manson was a favorite target. And I have to say, most of the things that were restricted or the target of potential restriction were pretty harmless, at worst.

Now, limiting speech seems to be a tool that’s been adopted outside the conservative sphere. But it has the same earmarks. It’s based on a morality. It’s kind of nebulous. We try to enforce it by punishing a few standouts who aren’t actually the problem, but they make good figureheads for the problem.

I’m less opposed to the ideals that are calling for the limiting of speech than the ones involved in limiting speech 20 years ago. But I’m still opposed to limiting speech as the mechanism for reaching any ideals.

When I say I care about intellectual freedom today, it’s not because I’m shedding tears for the conservative pundit who can’t speak on campus. It’s because I’m confident that while limiting speech is a tool held firmly by people I agree with, I still think it’s a bad tool, and that tool becoming powerful does not bode well for the future when it’s bound to exchange hands once again.

To me, it’s not about the freedom of 150 authors. It’s about the freedom of 150 million authors to come.