Today the Emmys were on. I know, I never thought I would start a blog with that sentence either. But amongst the talk of who was wearing who and what that meant for what, someone said something really interesting. Wait, dumb. Someone said something dumb. An interviewer asked a starlet about her favorite TV shows, and the starlet said, “[show x] is a guilty pleasure. I’m not ashamed to admit it.”

Wait a minute. If you’re proud to say you enjoy something, how is that a guilty pleasure? Isn’t that just a pleasure, to you at least? I think to some people, drinking may be a guilty pleasure, something that they enjoy partially because they shouldn’t, while to others of us it’s a full-on pleasure that isn’t pleasurable only when it’s purely medicinal.

Which brings us to the topic at hand: Chick Lit. Chick Lit, by my definition, is any book that is consciously marketed towards women as the primary audience. I’m also adding that these books deal with women, women’s issues, and have a distinctively female sensibility. They also tend to deal with these issues in a lighthearted fashion. Please note that no pieces of this definition have any sort of value judgment associated with them.

Fair enough?

A controversy of sorts started when a couple of bestselling female fiction writers (that is, writers who happen to be female and write fiction), Jennifer Weiner and Jodi Picoult, complained about the level of fame achieved by Jonathan Franzen and the extensive coverage of his newest book. Picoult supposedly started the whole thing on Twitter, the home of smack talk. I’m really upset that there was no Twitter a decade ago. Your Mama jokes are tailor-made for Twitter, and I think we wouldn’t have seen their tragic end quite so soon if we all could have used this social tool to mock each other’s mothers.

Picoult’s complaint was that Jonathan Franzen’s newest book, Freedom, was written up twice in the New York Times in one week. She felt that was unfair attention. Then, our friend Weiner jumps in. I wish there was some kind of mocking name I could assign her, but nothing really strikes me as funnier than Weiner, so we’ll stick with it.

Weiner then gets on Twitter and asks for people to Tweet their anti-Franzen sentiments. Let’s step back for a second and notice a key difference here. Picoult did not attack Franzen, nor does she blame him for this issue. In fact, in a later interview with Huffington Post, Picoult and Weiner both respond to their Twitter posts. Picoult is quick to point out that she has no animosity towards Franzen, plans to read Freedom, and fully expects to enjoy it as a book. Picoult’s issue is with a preponderance of coverage on what has been deemed “literary fiction” which she feels left out of, and that’s a fair complaint.

In the same interview, however, Weiner comes off as a complete dum-dum. Let’s look at a quote:

Why do you feel that commercial fiction, or more specifically popular fiction written by women, tends to be critically overlooked?

Jennifer Weiner: I think it’s a very old and deep-seated double standard that holds that when a man writes about family and feelings, it’s literature with a capital L, but when a woman considers the same topics, it’s romance, or a beach book – in short, it’s something unworthy of a serious critic’s attention.

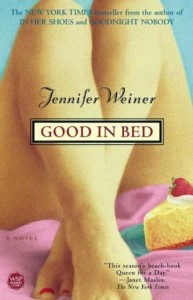

Really? That’s an interesting point. Let’s take a look at Weiner’s book Good in Bed:

Note the blurb: “This season’s beach-book Queen for a day.” Now, Weiner, if you’re upset about this beach book term, why is that blurb on the cover? Not only that, but why is it the ONLY blurb on the cover. Your blurb sells your book as a beach read, a seasonal as opposed to lasting hit, and uses the word Queen in a fashion that I don’t fully understand but that is clearly meant to attract a certain audience.

Let’s also make some notes about the cover’s design while we’re at it. Do I see cheesecake off to the side, barely jammed in the frame like it was an afterthought and we needed one more girly thing crammed in just to make sure? Do I see painted toenails? Okay, we do see a pair of legs, arguably interesting to men, but in reality more interesting to women. Disagree? Walk through the grocery store and see what’s on the cover of Shape magazine. A bikini-clad babe? Thought so.

The point is, if I’m looking at this in the bookstore, I’m not really sure why it would appeal to me as a man or a reader of literary fiction. I’m okay with that, and in fact if you’ve written a piece of fiction with women and beach readers in mind, that’s fine. I’d rather not waste my time picking up a book that was written for someone very different from myself. When you pitch your book as a beach read, knowing damn well what that means, I’m not going to consider it literary fiction. It doesn’t mean it’s a bad book, but if I’m looking for something character-driven and meaty, I’ll skip this one, and that is a direct result of your marketing. When you market a book as a beach read, you can’t be angry that people see it as such.

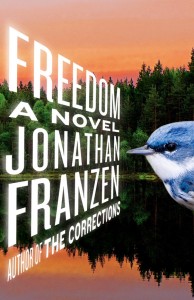

Because Mrs. Weiner brought up the comparison, let’s look at the cover of Franzen’s book:

To be honest, this seems far less targeted to a specific sex. A bird, the woods, and a lake. These pictures don’t scream male or female to me. The cover is also not really excited to convince me how to categorize this book. Are they taking the shocking position that I may actually have to pick it up to learn more about it?

It’s sort of like being a teacher and deciding between calling on two students. One is sitting in the chair and calling out the wrong answer while dancing around, the other is quiet, and though potentially just as wrong, at least trusts you to do your job and call on her.

I understand that authors don’t always have total control over the jackets their books wear. Just be prepared to accept that your book will get very little attention from men and women disinterested in beach reads if you make a cover that is calling out to women and beach readers. To paraphrase Dave Chappelle, your book might not be chick lit, but it’s wearing chick lit’s uniform. There’s nothing wrong with targeting an audience, but you need to understand that part of targeting one particular audience means moving your sights off another. If you target Twilight fans, you might sell more copies, but you won’t sell to a group of people who are opposed to that particular series, you won’t be taken as seriously, and the cost of some of that book rack success may be less attention from critics who see your book as pandering to a certain audience, a notion these critics got FROM YOUR BOOK.

Let’s not judge a book solely by it’s cover. Let’s take a look at a couple plot summaries:

Good in Bed, Library Journal:

Cannie Shapiro is in her late twenties, funny, independent, and a talented reporter for the Philadelphia Inquirer. After a “temporary” break-up with her boyfriend of three years, she reads his debut column, “Good in Bed,” in the women’s magazine Moxie. Titled “Loving a Larger Woman,” this very personal piece triggers events that completely transform her and those around her. Cannie’s adventures will strike a chord with all young women struggling to find their place in the world, especially those larger than a size eight. Despite some events that stretch credulity and a few unresolved issues at the end, this novel follows the classic format of chasing the wrong man when the right one is there all along.

Okay Weiner, I’m going to need you to explain to me how this is not falling into the stereotypical genre label of chick lit. Let’s see, you have a character who is a “funny, independent…reporter.” Wow, that’s a fresh one. The book has a strong subplot related to heterosexual relationships with men, a stance on whether or not it’s okay to be a larger woman, and “will strike a chord with all young women struggling to find their place in the world…” Oh, and the main character chases the wrong man when the right one was there all along? Christ, is that not the tagline for every lazy rom-com this side of You’ve Got Mail?

The book might be great. It might be well-written and structured. But for an author who is trying to legitimize her genre, Weiner sure doesn’t spend a whole lot of time creating something that demonstrates the legitimacy she’s looking for.

For the sake of continued comparison, let’s check out a review of Franzen’s Freedom and see if there might be any reason that it’s gotten more attention:

Readers will recognize the strains of suburban tragedy afflicting St. Paul, Minn.’s Walter and Patty Berglund, once-gleaming gentrifiers now marred in the eyes of the community by Patty’s increasingly erratic war on the right-wing neighbors with whom her eerily independent and sexually precocious teenage son, Joey, is besot, and, later, “greener than Greenpeace” Walter’s well-publicized dealings with the coal industry’s efforts to demolish a West Virginia mountaintop. The surprise is that the Berglunds’ fall is outlined almost entirely in the novel’s first 30 pages, freeing Franzen to delve into Patty’s affluent East Coast girlhood, her sexual assault at the hands of a well-connected senior, doomed career as a college basketball star, and the long-running love triangle between Patty, Walter, and Walter’s best friend, the budding rock star Richard Katz. By 2004, these combustible elements give rise to a host of modern predicaments: Richard, after a brief peak, is now washed up, living in Jersey City, laboring as a deck builder for Tribeca yuppies, and still eyeing Patty. The ever-scheming Joey gets in over his head with psychotically dedicated high school sweetheart and as a sub-subcontractor in the re-building of postinvasion Iraq. Walter’s many moral compromises, which have grown to include shady dealings with Bush-Cheney cronies (not to mention the carnal intentions of his assistant, Lalitha), are taxing him to the breaking point. Patty, meanwhile, has descended into a morass of depression and self-loathing, and is considering breast augmentation when not working on her therapist-recommended autobiography. Franzen pits his excavation of the cracks in the nuclear family’s facade against a backdrop of all-American faults and fissures, but where the book stands apart is that, no longer content merely to record the breakdown, Franzen tries to account for his often stridently unlikable characters and find where they (and we) went wrong, arriving at–incredibly–genuine hope.

There are a lot of chick lit elements present here. Strong female characters. Difficult romances. Family issues. So what separates this from a Weiner? I’d say that a careful look at the last sentence reveals a lot. “Stridently unlikable characters?” That is not something you see a lot of in chick lit. In fact, I would argue that chick lit is often about wish fulfillment, and an unlikable character who makes choices that conflict with the reader makes that connection difficult to create and maintain.

Look how much is going on here. We have politics, various menial jobs, the structure of the American family, more than two principle characters, and an emotional journey in the story that is not just about empowerment. Although the review is longer, I still feel like there is far more left to explore in Franzen’s book while I feel that Weiner’s is pretty well laid-out.

Having not read either book, I don’t want to say much more about the contents beyond what was said by reviewers. But I will say this: If you want people to review your book with some depth, there has to be some depth to your book. People may pick it up on the strength of your previous books and for pure pleasure reading, which is a great thing and should not be looked down on. But how much review does a book like Good in Bed require, and what else can be said without giving it all away?

In the Huffington Post interview, the more humble (and, ironically, more successful) Jodi Picoult is fairly reserved and more reasonable throughout. She is careful to point out that she has no animosity towards Franzen, reserving her criticisms for the New York Times. She also hesitates to bring up specific authors, unlike Weiner who decries the fact that she is less famous than Nick Hornby. Nick Hornby! Even when the interviewer brings up the specific example of trashy thriller writer Lee Child’s success and consistent attention, Picoult is diplomatic and says that the Child phenomenon is likely “an anomaly.”

Weiner, however, just keeps rattling. When the above case of Lee Child comes up she says, “The examples you cite reinforce my argument that women are still getting the short end of the stick. If you write thrillers or mysteries or horror fiction or quote-unquote speculative fiction, men might read you, and the Times might notice you. If you write chick lit, and if you’re a New Yorker, and if your book becomes the topic of pop-culture fascination, the paper might make dismissive and ignorant mention of your book. If you write romance, forget about it. You’ll be lucky if they spell your name right on the bestseller list. I think I remember seeing one review of Nora Roberts once, whereas Lee Child can count on all of his books getting reviewed. This strikes me as fundamentally unfair.”

Well, Ween, can I call you Ween? Ween, the thing is, as a librarian and someone who is very aware of what goes out and to whom, I can say with confidence that women read as much, if not more, Lee Child than men do. So the idea that women are somehow being shortchanged is just not true. Because book reviews are for readers, not writers, and if tons of people are reading Lee Child, you better review the new Lee Child. And if as many or more women are reading Lee Child, how are you serving them by forcing them to read reviews of chick lit? Not to put too fine a point on it, but if you had a paper with space for ten book reviews, wouldn’t you try to put in reviews that would include the maximum number of readers? You can choose to write for women, and that’s a legitimate choice, but stop being disappointed that people interested in selling papers don’t give you the time of day when you elect to alienate half of their audience. And you need to stop using the word “unfair” if you expect to be taken seriously. How is replacing a Lee Child review with a review of your book fair? And if fairness were a real concern, every book would have to be thrown into a huge pile and the New York Times would pull ten random titles out each week. But what would be the point of that?

By the end of the Huffington Post interview, the cadence becomes pretty clear: Question, reasonable and measured response from Jodi Picoult, bizarre rant from Jennifer Weiner. The result? Well, if I were picking between a Jodi Picoult book and a Jennifer Weiner book, it would be Picoult all the way. She at least seems to have her own thoughts worked out and to have something to say that, though I might not always agree, I can at least understand. Her overall point is that people don’t have to pick between something popular and something literary, that it’s a false choice. She also points out that popular fiction is important because books we consider classics today were often considered popular fiction in their own time. Very true and well said. I agree that something being popular does not make it inherently trashy, just the way that I song I loved sounds just as good regardless of wheter it’s never been on radio or find itself in constant rotation.

Weiner, on the other hand, uses the interview as a soapbox to call out specific authors that she feels have somehow sleighted her by doing their own work and being more famous. She sounds like the annoying kid in school who is angry because the football team gets all the attention, something that sucks and is true, but rather than offering solutions or advice she takes this interview as a chance to start trouble with others. It’s a lot like what you see in the rap world when a middling rapper will declare that he has a beef with Jay-Z or 50-Cent. But there’s no beef. It’s all just a way to associate your name with someone else and therby hope to eleveate yourself.

Weiner cites Nick Hornby as an example twice, and she makes no bones about the fact that she feels that she deserves the same amount of attention that he does. Let’s do a quick breakdown of the numbers here:

Quick Scoreboard:

Nick Hornby: 16 books, editor of 4 anthologies, 5 film adaptations.

Jennifer Weiner: 8 books.

So, even throwing out writing quality and across the board appeal, Hornby has done more than twice the work that Weiner has. Whether or not he had more opportunity as a man is up for debate, but I would argue that being a non-American is as much a handicap for success in today’s U.S. book world as being a woman. It makes Jennifer Weiner look like Jennifer Whiner, and until she’s got a body of work that’s somewhat comparable to Hornby’s she should make wiser choices of who she compares herself with.

This whole controversy first came to my attention because of an article, “Women Are Not Marshmallow Peeps, And Other Reasons There’s No ‘Chick Lit’ The ultimate point of the article:

“The term “chick lit,” as I mentioned today on Twitter as I was composing this entry, increasingly makes me feel like I’m being compared to a marshmallow peep just for reading books by and about women. I know what romance novels are — I read some of them, I dislike many of them. I know what shoe fiction is, in my own experience — it’s fine, but it’s not very nourishing. There are subgenres within commercial women’s fiction that are real and identifiable.

But I don’t know what “chick lit” is anymore, except books that are understood to be aimed at women, written by women, and not important. And I can’t get behind that.”

Well, confused writer, I can tell you what chick lit is. It’s not about chicks writing it, and it’s not about chicks starring in the stories. It’s about the book being marketed to chicks, and marketed in such a way that it forces men (and uninterested women) to take an almost aggressive stance of non-readership.

I just read Sloane Crosley’s How Did You Get This Number? It has all the earmarks of Chick Lit. Young lady living in New York, stories about love, discomfort in the woods of Alaska. Is it chick lit? Maybe. But I liked it. And I didn’t feel like it was marketed in such a way that it was excluding me. It wasn’t a shoddily-built clubhouse that whipped up interest by hanging a “No Boys Allowed” sign on the door. It was funny, poignant, and had scenes of real emotion that may not be experienced by me as a man, but were related to me in such a way that I felt like Crosley was helping me understand her feelings rather than saying, “It’s a chick thing. You wouldn’t understand.”

In opposition, let’s look at Good in Bed. I’m comfortable in my own skin, but I don’t want to be seen reading this book. Why? Because it feels like I’m reading something that was marketed at my expense, marketed as this secret sisterhood that I’m not a part of. Reading it makes me a tool. It would be like putting a politician’s sign in my yard despite the fact that the politician was running on an anti-white-male platform. Being a white male isn’t the most important part of my identity, but I can’t deny that it’s there, and trying to deny it makes me an idiot.

The real issue here is not the chick lit label, not the number of reviews a writer gets, none of that. It does suck that Franzen gets reviews as that means he’ll sell more books while writers who may not otherwise sell books are denied that space, but that’s not a battle you can fight by taking down Franzen or the New York Times.

I would pose this theory: in a free market of books, the ultimate enemies of good taste are the people who profit from bad. There’s plenty of room for lovable dopes and garbage entertainment. I would point to the Scary Movie/Epic Movie/Vampires Suck franchise, which despite being universally shit on makes more than enough cash that they will keep cranking them out. Until you stop supporting them, and until you turn people on to something better, we can expect year after year of crap.

This is also a battle you have to fight yourself and with your own level of comfort enjoying the things you enjoy. You have to learn to accept yourself and your personal tastes. If someone says the book I’m reading is chick lit, and I’m enjoying the book, I won’t waste my time convincing them that they’re wrong and that this book has a hundred good qualities. Because I’m comfortable, and if someone wants to give me shit about my reading choices I’m comfortable in telling them to fuck themselves. I don’t need to convince someone that I’m right. I know what I like regardless of how it may be labeled by someone else who probably hasn’t even read it. Maybe it’s about the label for some people. As a comparison though, I don’t give a fuck if a CD at the record store is shelved in Pop or Rock. It’s not important to me because the enjoyment I find isn’t in standing around the record store and having other people see me there. It’s in the songs.

The most frustrating part about this is the fact that it is a weiner who clearly writes chick lit making the whole thing about men vs. women when her books are marketed in such a way that she profits from that conflict. There are so many great women writers out there who write books about women. Amy Hempel, Mona Simpson, Grace Paley, Joyce Carol Oates, Katie Arnoldi, Sarah Vowell, Kay Ryan, Katherine Dunn, Toni Morrison, Isabel Allende, Amy Krouse Rosenthal, Aimee Bender, Joan Didion, Trinie Dalton. There are lots of great books that could be chick lit but walk freely outside that category on the strength of their writing, such as Like Water for Chocolate, A Girl Named Zippy, The Glass Castle, Mommies Who Drink, and Microthrills.

The distinction is that these books don’t fall outside chick lit because the authors complained, raged against the label, or fought against other popular authors for market recognition. They are great pieces of writing, and the books themselves do all the necessary arguing. When explaining why these books are not stereotypical chick lit, one could point to the text rather than outside of the text, to the “media” or various institutions.

As Jodi Picoult pointed out, there is a false choice set up that makes us believe we have to choose between popular fiction and literary fiction, that those two genres are inherently opposed. She was right, this is complete horseshit, and today’s popular fiction is tomorrow’s Wuthering Heights. But the other line we’re being fed by these articles is that there is a choice to be made, that we must either abandon chick lit or legitimize it. I say that’s a false choice as well. I say that something is legitimized on its strength as literature and it’s sales, not by arguing about terminology. I say read whatever the hell you want, and don’t feel bad about it. Maybe some asshole who reads Nietzsche made you feel guilty for reading Bridget Jones’ Diary. Fuck him. People who want to bash on your reading selections don’t deserve your consideration or the effort it takes to win them over.

As far as Weiner goes, she needs to pick her battle more carefully. I agree that there is nothing wrong with beach reading, pleasure reading, and reading that is the literary equivalent of reality TV. If it makes you laugh, if it reaches you on some emotional level, or if it makes three hours of waiting room time fly by, that’s fine, and the book has succeeded.

What Weiner doesn’t understand is that there is room for this kind of thing, and plenty of it, and that space doesn’t have to be manufactured by elbowing other writers and books to the side. It will not be made by trying to raise the esteem of genres and types. The way to make room for chick lit is to give people the message that it’s okay to read anything, and to then go about writing the best books you can and quit worrying about what Nick Hornby is up to.

The part that is really baffling is the fact that Weiner has now been on Huffington Post, NPR.org (twice) and tons of other news outlets. What makes this so hard to swallow is that she is complaining about another book, and somehow her COMPLAINTS about a book are receiving the amount of attention afforded to an actual book, an actual piece of work. It saddens me that someone can complain about the space afforded to another’s book, meanwhile dominating just as much space with said complaints and ultimately empty content that argues over whether or not one label is appropriate. If I were looking to get a book reviewed, I think I’d be more pissed off at Jennifer Weiner, an author riding a controversy rather than her abilities, than I would at Jonathan Franzen, an author with a product who does not control the number of articles printed about him.