Made it through issue 113 at the laundromat last night! At first I thought that maybe the squalor of the place was the key. Really, focusing on anything else is a real freakshow.

Last week when I went, I was trapped in a small hallway created by industrial washing machines, and standing in the center was a woman with a tiny body and giant boobs. I’m pretty sure there was no way to get by her without rubbing (probably my crotch or butt, depending on my orientation) on her boobs.

I’m not one to immediately point out the hazards of large breasts. But in this situation, small warm laundromat, kinda rough.

Although that paled in comparison to last night. I decided to go super late. It’s a 24-hour joint, so how many people could be there at 11PM on a Sunday? Well, one it turns out. One homeless woman sleeping on the folding table. I’ve long railed against folding laundry at the laundromat instead of at home. So if you need a good reason besides just getting me riled, I’d put near the top the fact that you are folding your clean clothes on the bed of a homeless woman.

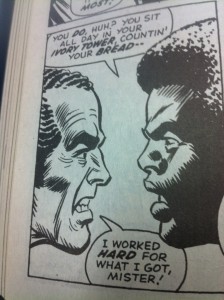

(I’m with you, generically angry black guy. It must be night to sit in an ivory tower, which probably also has a laundry facility of some sort)

(I’m with you, generically angry black guy. It must be night to sit in an ivory tower, which probably also has a laundry facility of some sort)

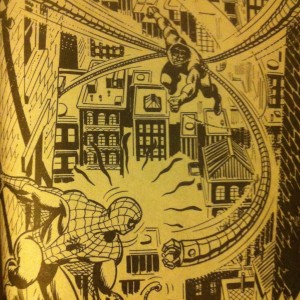

You know what? I’m starting to think that it’s not just an irrational fear of the homeless and how they represent en eerie possible future, nor is it the danger of being smothered in giant breasts that has made these comics so great. Somewhere around issue #100, they’re actually…good.

I mean, even in black and white, even with the dated cultural references, they’re pretty thoroughly readable. You get something out of them.

I mean, even in black and white, even with the dated cultural references, they’re pretty thoroughly readable. You get something out of them.

Okay, they aren’t exactly doing the work of poet laureate dudes or anything like that, but they have more depth than I expected. Specifically, in one relationship. The one between Peter Parker’s girlfriend Gwen Stacy and the doddering, doting Aunt May.

(I lamented not taking a photo of these two panels. Then I figured, this must be ALL OVER the google)

(I lamented not taking a photo of these two panels. Then I figured, this must be ALL OVER the google)

In one scene, Gwen Stacy calls out Aunt May for being, well, the Aunt May we’ve all come to know in the comics. The one who Peter fears will have a heart attack if he does stuff. For some reason.

I’m sorry, but if I told my mom that I was a superhero, or even a villain of some sort made out of sand, and she dropped dead, I would think this probably had a lot to do with her previous lifestyle choices as opposed to just being REALLY surprised.

Anyway, Gwen and May have a little fight wherein Gwen tells May that she’s basically a co-dependent and that neither her or Peter will grow until she can let go.

Okay, again, it’s not some broad trying to wipe up imaginary blood from the floor, or some runaway punk on a log boat with an enslaved black guy, but it’s still kind of interesting and has more depth than I expected.

What it really does, though, is make me lament the way the movies have been. I think it brings into stark contrast what the problem is with them.

Every time a superhero movie comes out, a friend will ask if I’ve seen it. And the answer used to always be “Yes, idiot. Of course!”

Now, the answer is “No, idiot!”

I wasn’t calling people idiots because they didn’t know where I stood with movies. I’m just generally an asshole.

The thing is, I’m just less and less interested. And here’s why:

Every superhero movie is origin. And if it’s not, it’s a little too origin-adjacent for my liking.

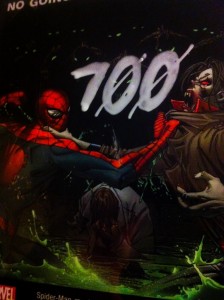

Let’s put it this way. There are 700 issues of Amazing Spider-Man. That’s just Amazing Spider-Man, mind you. Now, guess, based on how the movies have gone, in which issue Peter Parker graduates high school.

One who knows a little about the movies would guess…250? Something like that? I mean, they’ve made a bunch of movies, and in those it seemed like he was in high school at least twice.

Well, it’s issue #28. Yep. 28 out of 700. So, doing the math, the Amazing Spider-Man is in high school for 4% of his appearances.

It’s not necessarily a problem in itself. Brian Michael Bendis’ Ultimate Spider-Man kept Peter Parker in high school for its entire run. And I loved it.

The problem is that the movies really seem into the origin, and there’s just SO MUCH other great source material out there to explore.

There are a few basic problems with going with the origin for the movie. But we’ll get to those in a second. First, I want to address what I consider to be a falsehood in movie-going audiences, and it’s this:

If we don’t show the origin, the audience will be lost.

Really? Because from what little I know about storytelling, this probably isn’t true.

Let’s take the most recent Superman movie. If I asked about Superman, I’m guessing 60% would be able to tell me he came from Krypton, yada yada. 90% would probably know he’s a superhero who flies and is really strong. So why do we have to SEE all that shit? AGAIN!!!

Not to mention, a legitimate storytelling technique would be to let some things be surprises to the audience as well as the other characters. If I walked into a movie where a man was flying in a red cape, smashing through walls and bending steel, how upset am I going to be if he breaks out eye lasers without warning? How about a surprise here and there, goddamn it?

Okay, so I have to say that I think people would get it. With just a little hand-holding, they would get it.

So let’s switch to talking about the big problems with origin stories.

1. If it’s the origin of a character we’re familiar with, the mystery parts are a groanfest.

Yes, you can stick to walls. This movie is called motherfucking Spider-Man. SPIDER-Man. So while you seem surprised about all this, I’m sitting here, very aware that I’m sitting and watching a movie, destroying my GI tract in a quest to eat enough popcorn to make up for the poor experience here.

2. The parallel villain origins are almost always weak.

People really enjoyed the Chrisopher Nolan Batman flicks. But what’s with Liam Neeson wanting to blow up Gotham? Why? What’s the point?

Oh, right. The point is that they have to have some constructed conflict so we can make sure they karate each other.

3. It restricts your ability to create a story of more depth.

You’ll notice that a lot of movies, regular non-super ones, don’t spend a shitload of time explaining how a person became the type of person they are. You don’t watch Rocky and actually see him boxing as a young man, full of wasted potential. No, you get the idea as you go. It takes so goddamn long to set up this scene where someone gets bit by a spider that we miss out on other stuff.

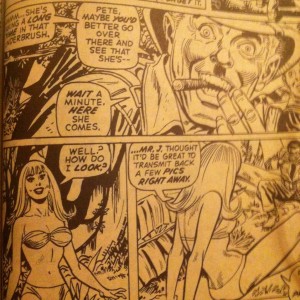

(J. Jonah Jameson: Early adopter of filth as content)

(J. Jonah Jameson: Early adopter of filth as content)

4. It separates the movie-going audience from the characters in the movie.

This is something that always happens in zombie movies made before the last 5 years or so. Zombies are real as a concept. If I say “zombie” to you, you know what I’m talking about. Yet, when they come to life in movies it’s as though nobody has EVER heard of such a thing. So we have these asinine conversations about “What are these things?” “I don’t know, but they sure look -ah!- HUNGRY!”

Kill me.

It’s nicer when the audience and characters are more on the same level. Or even, god forbid, the characters are a little ahead of the audience. Horror movies were the first to figure this out, I think. To have you, as viewer, experiencing things in real time with the characters.

(ah, quicksand. Ubiquitous in the 70’s)

(ah, quicksand. Ubiquitous in the 70’s)

~

Anyway, that’s a long rant about movies in a review of a book. But the point is, I was surprised that there was any depth to these things, and that’s sad. Why should I be surprised? Shouldn’t that be the expectation? And would it be such a tragedy if some of that complexity came into the movies?

Could we have one superhero movie that’s not about where the characters came from and more about where they’re going?